“Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

— Mary Oliver

Politics

I was going to title this piece “Why Trump Is Stupid.” Then I thought that the real problem is that we’re being taught to be stupid by the coterie of Trump’s stupid agents. But both Trump and his people will be gone one day, and the real problem is that we don’t distinguish stupidness, which is a choice, from shortsightedness, which is a habit. And so I settled on the title above.

Being shortsighted is relative to the issues at hand. The traditional “long view” of wisdom is generations longer than the time frame most of us adopt. There is an insidious economic incentive to look no further than the next election, policy objective, or shareholder horizon. And since how far we look ahead is essentially dictated by the extent of what we take to be the relevant future, we only look ahead as far as things concern us.

This amount of foresight is insufficient when dealing with events that unfold over the long term, but whose immediate impacts don’t reflect the long term possibilities. Immigration is a great example.

When the country needed low wage workers, and the world had a surplus wanting to come to the US, immigration benefited everyone. The short-term cost of housing and caring for new immigrants was within the time frame of the economic reward they would provide. The East Coast became a welcome center. Communities, job opportunities, and cultural benefits, while not coordinated, were appreciated both within and without the immigrant communities.

The West Coast also saw an influx of Latin and Asian immigrants, but they were neither as welcome nor as easily assimilated. While the Europeans brought relevant knowledge, culture, art, and history, the Asian and Latin American contributions were less appreciated and less affluent.

These immigrants took the lowest paying jobs in the least important corners of Western culture. Indigenous and Asian philosophies had no place in progressive Western culture in the early 20th century. They still don’t, except now Asian progress in science and politics has passed the point of equality with the West and is moving into the lead.

Trump is spearheading this decline of the Western world, but this has followed decades of poor leadership and dumb decisions. To borrow a quote from Isaac Newton, “If our actions are shortsighted, it is because we have stood on the shoulders of midgets.”

Physics

I will illustrate shortsightedness with an example from physics. A defining characteristic of shortsightedness is that it doesn’t seem shortsighted when you’re only looking at what’s immediately in front of you. Shortsightedness is only apparent, and only has meaning, when you have a longer view. If all you can see is one step ahead, then there is no long view, there are only unjustifiable pronouncements about unforeseeable futures.

In 1935 the senior Albert Einstein and his juniors Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen co authored a paper that fundamentally criticised the approach that was being put forward by the then-new field of quantum mechanics. They said that if energy was conserved, and if a mass in motion has energy, then when a stationary object fractures and flies apart in two opposite directions, you must be able to tell exactly the position of one of the two pieces from the measurement and position of the other.

Einstein had only come to the US two years before and his English was not that fluent, so he let Rosen and Podolsky write the paper. He grumbled that the result was not entirely what he meant to say as it didn’t make the point he was aiming for.

His objection has since been cast as referring to quantum mechanics as relying on “spooky action at a distance.” This mistranslation of his word “spukhafte” as “spooky” when a better translation is “haunted” misdirects his objection. Spooky implies the supernatural, while haunted means there is something unseen. Nevertheless, the EPR paper became a benchmark for objections to the new quantum theory.

Quantum theory blossomed into a hugely successful field. The somewhat vague objections of EPR were brushed off by garbled excuses known as “the Copenhagen interpretation” that didn’t address the issue. Careful interpretation has never been a strong point in physics.

Twenty years went by during which no one addressed the EPR “paradox” and it was considered poor form to pay attention to the objections of old men. As a result of his continued objections, Einstein himself was socially and academically shunned by the physics community.

Quantum Mechanics

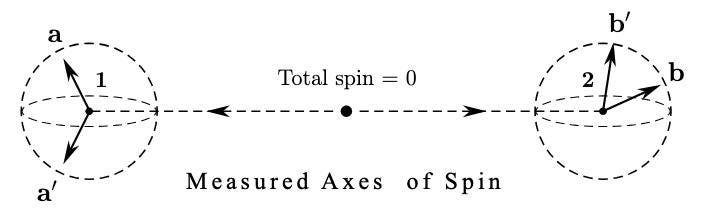

In 1951 David Bohm recast the EPR paradox in terms of the decomposition of spinning particles. He proposed a thought experiment using oppositely spinning particles that he claimed more clearly illustrated the core issues of the EPR paradox.

What was clear in Bohm’s reformulation was that remotely distant things affect each other through no known mechanism. We could say exactly what the effect was, so things could be accurately predicted, but there was no explanation of how. There was an outcome without a mechanism.

This reformulation was not the EPR paradox, which was an objection to the uncertainty principle. Instead, Bohm now presented an objection based on the observed correlation of widely separated objects for which quantum mechanics provided no mechanism.

Tim Maudlin (2014) explains that both EPR and Bohm dealt with both the issues of indeterminism and causality, they just emphasized different aspects of it. Nevertheless, the Bohm-EPR paper became the new benchmark for objections to the now well-established quantum theory.

Then, in 1964, John Bell published his now famous paper in which he hoped to endorse the EPR conclusion of the insufficiency of quantum mechanics in the context presented by Bohm-EPR. That is, he hoped to show that there must be some mechanism that was absent from the current theory.

Instead, and to his dismay, he showed the opposite. He claimed to prove that there was no way to make quantum mechanics sufficient by having local effects result from local causes. In the context of the EPR paper, which was vaguely framed, this was not emphasized. The recontextualizing by David Bohm brought this conflict to the fore. Maudlin notes that Einstein greatly appreciated this change in emphasis, which only strengthened his objection to this aspect of quantum mechanics.

Bell’s paper recast the issue in a context that could be tested with experiment, and this revitalized interest in the EPR question, which had never been seriously addressed. In the 1970s young physicists debated these questions and began to design experiments to test them. This was the quintessence of scientific progress even though Bohm’s reformulation didn’t address the whole EPR question, and even if Bell’s conclusions were wrong.

Showing False, What Was Claimed True, About What Was Insufficient

How farsighted are you? Explore your future with a free call. Talk to me!

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Stream of Subconsciousness to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.